Germany’s energy transformation policy – Energiewende – is creating more than a million new jobs by embracing innovative technologies and services.

While the energy situation there is very different – just 30 per cent of the country’s generation was renewable last year – there are lessons New Zealand can draw as it seeks to decarbonise its economy, BusinessNZ Energy Council policy advisor Tina Schirr says.

The German government’s support for research and development in renewables and battery technologies is expected to create 1.1 million jobs, including about 350,000 already created up to 2015.

Schirr says Energiewende is seen as a longer-term “investment” which comes with significant costs. The German government has spent about €500 billion on electricity subsidies to date. But it expects it will have beneficial outcomes out to 2030 in terms of economic development, as well as by creating a decarbonised energy system.

Germany’s “integrated” policy seeks to lower emissions across the country’s electricity, industrial and transport sectors. It also seeks to increase energy security by reducing the country’s coal, gas, petroleum and uranium imports.

Energiewende was initially introduced in 1990 but has been amended several times as technology and the market has developed. The most recent changes were introduced last year, switching from fixed feed-in tariffs to competitive auctions for renewable generation to encourage more cost effective investments. It also promises a smart meter roll-out and a capacity reserve market to encourage greater in-country management of its electricity supply.

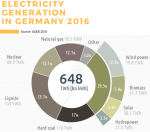

Germany last year generated 85 terrawatt-hours of electricity from nuclear plants -13 per cent of its total. Lignite production accounted for 150 TWh, followed by 110 TWh of generation from hard coal plants. About 30 per cent of its generation was renewable.

Targets, comparisons

Schirr was the latest speaker in the Smart Grid Forum’s series of talks on new energy technologies and the various approaches being taken to their adoption here and globally.

She noted that while Germany’s electricity sector emissions are decreasing, there has been little change in its transport and industrial sectors since the 1990’s.

That stagnation will make the target of a 40 per cent emissions reduction by 2020 “hard to reach with three years to go”. But she believes that attaining a 55 per cent drop in carbon discharges by 2030 is possible. New Zealand’s commitment to reduce its emissions 11 per cent by 2030 is much less certain, Schirr believes.

But Germany is starting from a low renewable energy base. Its electricity production is about 30 per cent renewable. Including industrial energy and transport drops that to just 13 per cent. In contrast New Zealand’s electricity production rose to about 85 per cent renewable last year and overall energy consumption was about 40 per cent renewable.

Schirr says Germany’s last coal-fired generators are expected to be closed in 2038, if the trend continues. New Zealand’s two remaining coal units at Huntly are currently projected to be decommissioned in 2022.

However, Germany’s population of 81.4 million has per capita emissions of 11 tonnes per year compared with 17 tonnes per year in New Zealand.

Schirr predicts New Zealand is more likely to meet its target of 64,000 electric vehicles on its roads by the end of 2021. While there are only 3,800 EVs in New Zealand so far, they account for about 1 per cent of monthly registrations.

Germany’s take-up of the technology is at a much lower rate, she says, possibly because the country’s car industry is heavily invested in its aftermarket sales and service model. It has only about ‘s 75,000 EVs on the road, despite an ambitious target of 1 million EV’s by 2020.

Policy implementation

Germany last year overhauled its energy policies, launching what it has hailed as the “electricity market 2.0”. That aims to encourage the use of smart technologies and market approaches to encourage the uptake and integration of renewables on the country’s grids.

Speaking in Wellington last week, Schirr says the “integrated” policy tackles emissions reductions across the electricity, industrial and transport sectors. Energy security is a key concern for Germany and it is encouraging more off-shore wind development in coming years, Schirr says.

That is seen as a much more reliable resource, “generating almost every hour” compared with wind farms on land.

Energiewende is also using markets to ensure security of supply. The policy seeks to stimulate more market competition and innovation to help provide the flexibility needed to deal with the fluctuations of renewable production.

That includes ensuring that price signals reach consumers to ensure that the lowest-cost options are used. Alongside that is a policy that scarcity will be signalled and a principle that the government won’t intervene on setting prices.

It is also seeks to establish a separate capacity reserve to help provide security of supply.

Timely, flexible policy

The Energiewende also seeks to use markets to resolve its “nuclear issue”. Germany decided to close its nuclear power plants following the Fukushima reactor meltdown in 2011. Schirr says the seemingly fast policy change soon after the tsunami-triggered event followed decades of public uncertainty about the technology.

There have been several key changes to the policy since 1990. Schirr says while there has been near constant policy changes, a “timely and flexible” approach also allows the country to adapt to new circumstances and technology developments.

She says there have been some less than ideal outcomes. Germany previously prioritised coal generation ahead of more efficient fast-starting gas units, several of which have closed. The value of incumbent utilities, such as RWE and E-On, reliant on nuclear and gas-fired plants, have also been slashed.

The latest iteration of the Energiewende policy provides funding to help safeguard those plants in future.

Citizen’s energy company

Schirr says more than half of a German electricity bill is made up of surcharges and taxes.While the cost of electricity is comparatively high, “this is what we pay for our Energiewende”.

Electricity in Germany is about 29 Euro cents per kilowatt-hour, on average, compared with an equivalent of about 17.6 Euro cents for New Zealand households, Schirr says.

But she notes the average German household uses about half as much electricity annually – about 3,360 kWh compared with more than 7,200 kWh in New Zealand homes. That is partially due to the much wider use of gas heating or district heating schemes, but also reflects much more energy efficient buildings.

Schirr says last year’s policy changes also sought to simplify the terms for the “citizen’s energy company” – about half the investment in renewables comes from citizens.

It also supports innovation developments which will support peer-to-peer schemes, EV grants and funds the research and development of battery and hydrogen technologies.

Roof-top solar remains an important part of the Energiewende transition – last year solar accounted for 38.3 TWh of electricity production. Solar is important with the four largest energy utilities owning only about 5 per cent of the renewable energy installed in Germany.

Schirr says the revised policy acknowledges that subsidies can “harm” small-scale solar and cooperative companies. The high feed-in tariff – originally set at about 45 cents per kilowatt-hour – was slashed to about 15 cents/kWh in 2012, and about 10 cents/kWh in last year’s reforms.

“It is now looking for more competition with industry.”

Email: